If you’ve ever stood in front of your overflowing bookshelves and wondered, “How many books make a library?”, you’re not alone. It’s one of those questions that seems straightforward until you actually try to answer it. Does owning 100 books count as a library? What about 500? Is there some magical threshold where a personal collection transforms into something official?

The truth is, most of us are looking for a simple number. We want someone to tell us that 1,000 books makes a library, or that you need at least 5,000 volumes before you can legitimately call your collection by that name. But when we focus on the purpose behind a collection rather than arbitrary numbers, we start to see what truly matters. For authors looking to turn their ideas into meaningful works, the guidance and professional support from UK Publishing House can help transform a manuscript into a published book, ensuring that the story reaches its intended audience.

But here’s where things get interesting, and perhaps a bit frustrating if you came here looking for that magic number. The real answer is that how many books are in a library isn’t actually what defines it as a library at all. Focusing solely on quantity misses the entire point of what libraries have represented throughout human history: organised knowledge, intentional curation, meaningful access, and service to a community or purpose.

This narrow obsession with numbers obscures something far more valuable. It keeps us from understanding what truly separates a random pile of books from a functioning library, whether that’s the Library of Congress or a carefully organised shelf in your study.

So what does it actually take to create a library? What are the fundamental characteristics that matter more than raw volume counts? And if you’re building your own collection, whether for personal use, family education, or community benefit, what principles should guide you?

This blog will walk you through the real criteria that define libraries across all their diverse forms. We’ll explore everything from massive institutional collections to micro-libraries that serve entire neighborhoods with fewer than 100 books. You’ll learn what professional library science says about how many books to be considered a library, but more importantly, you’ll understand why that’s only a small piece of a much larger picture.

By the end, you’ll be equipped to appreciate libraries in their truest sense, and perhaps even build your own meaningful collection guided by purpose rather than arbitrary numbers.

Defining ‘Library’: More Than Just Books

Formal Definitions: Institutional & Legal Perspectives

When organisations like the American Library Association (ALA) or the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) define what constitutes a library, they’re not primarily concerned with counting volumes. Their criteria focus on structure, purpose, and professional standards.

From an institutional standpoint, a library requires several key elements. There’s a dedicated physical or digital space designed specifically for housing and providing access to materials. Professional or trained staff manage operations, assist users, and maintain the collection. There’s consistent funding, whether through taxes, institutional budgets, or endowments, that supports ongoing operations. Most critically, there are formal collection development policies that guide what materials are acquired, maintained, or removed.

These aren’t arbitrary bureaucratic requirements. They exist because institutional libraries serve defined communities with specific needs. A university library supports academic research. A public library serves its municipality’s residents. Each has obligations that extend beyond simply accumulating books.

When people ask how many books do you need for a library from this formal perspective, the answer depends entirely on the institution’s mission and the community it serves. A small rural public library serving 2,000 residents might operate effectively with 10,000 carefully selected items. A major research university library serving 40,000 students and faculty might need millions of volumes, specialised databases, and extensive archives.

Informal Definitions: Personal & Community Collections

Step outside institutional frameworks, and the definition becomes more fluid, but not meaningless. The concept of a “home library” or “personal library” is real and valuable, even if it doesn’t meet formal institutional standards.

Here’s where many people struggle. You might own 2,000 books. Your friend might own 500. At what point does a personal book collection become a personal library? Is there a specific threshold where how many books count as a library in the informal sense?

The distinction isn’t primarily about volume. It’s about intent and organisation. A large personal collection, even thousands of books, might just be accumulated possessions if they’re disorganized, inaccessible, or serve no clear purpose beyond “I like having books.” Conversely, a smaller collection of 300 volumes, carefully curated around specific interests, systematically organised, and actively used for learning or reference, functions as a genuine personal library.

Think of it this way: someone who buys every bestseller but never organizes them, rarely rereads them, and couldn’t easily locate a specific title has a collection. Someone who thoughtfully selects books aligned with their interests, organizes them logically, maintains records of what they own, and regularly uses them for reference or pleasure has created a library, even if the actual count is modest.

This matters because people often feel their collections aren’t “enough” to qualify as libraries. They’re stuck on numbers when they should be thinking about function.

Functional Definition: Purpose, Organisation, & Accessibility

This brings us to what might be the most useful definition: a library is a purposefully organised collection of information resources made accessible to a defined user group.

Let’s break that down.

Purpose means the collection exists for a reason beyond accumulation, education, research, entertainment, community building, preservation of knowledge.

Organisation means materials are arranged systematically so they can be found when needed.

Accessibility means the intended users can actually discover and use what the library contains.

These three elements work together regardless of scale. A 50-book collection organised by subject, catalogued, and shared amongst neighborhood families can function as a micro-library. A 10,000-book personal collection that’s unsorted, uncataloged, and effectively unusable might not function as a library at all.

For those considering starting their own library of carefully curated books, or for anyone looking to fine-tune their personal or community library, proofreading is an essential skill. Just as a library benefits from intentional organisation, a collection of written work thrives with the precision that proofreading provides. If you’re looking to help others refine their written content, learning how to become a freelance proofreader can offer a rewarding path.

Expert Tip: Prioritize Purpose Over Quantity. Define your library’s mission first; the number of books will naturally follow its intended purpose and target audience.

This functional definition frees you from worrying about how many books does it take to make a library in some absolute sense. Instead, you can focus on what actually matters: Is your collection serving the purpose you’ve defined for it? Can you and your intended users find what you need? Is it organised in a way that makes sense for how it will be used?

Emphasising Accuracy and Transparency in Definitions

Throughout this blog, we’re distinguishing clearly between formal institutional standards, informal personal practices, and functional definitions. When we cite collection size ranges, these are approximate guidelines based on publicly available data from library associations and individual institutions. They’re not rigid requirements.

Libraries exist on a spectrum. A collection of 500 books thoughtfully organised and actively used has more “library-ness” than 5,000 volumes gathering dust in boxes. Understanding this helps you make informed decisions about your own collection rather than chasing arbitrary benchmarks.

The Myth of the Magic Number: Why a Single Count Doesn’t Exist

Debunking the “Minimum Book Count” Idea

Let’s address this directly: there is no universal threshold for how many books to make a library. None. The idea that you need exactly 1,000 books, or 500, or 10,000, or any other specific number is fundamentally flawed.

Why do people want this number to exist? Because it would be simple. We could check our shelves, count our volumes, and know definitively whether we’ve “made it” to library status. But this desire for simplicity ignores everything that actually makes libraries valuable.

Consider two scenarios. Person A owns 3,000 books purchased impulsively over decades, stored haphazardly across multiple rooms, with no organisation system and no clear sense of what they actually own. Person B owns 400 books, each selected deliberately to support their work as a historian specialising in mediaeval England, organised using Library of Congress classification, catalogued digitally, and regularly consulted for research and writing.

Which is the library? By pure numbers, Person A wins. But functionally, Person B has created something far closer to what we actually mean when we talk about libraries. Person B’s collection serves a clear purpose, is organised for effective use, and operates as a genuine research resource. Person A just owns a lot of books.

This isn’t to diminish large collections. Size can be valuable, more volumes often mean broader coverage, greater depth, more diverse perspectives. But size alone, divorced from purpose and organisation, doesn’t create a library any more than owning 1,000 ingredients makes you a restaurant.

When creating a library or personal collection, the size and format of the books you include matter more than you might think. Choosing the right dimensions can enhance both the visual appeal and usability of your collection. To help authors and publishers make informed decisions, we’ve also written a detailed guide on “The Definitive UK Guide to Standard Paperback Book Sizes & Dimensions.” In that blog, we explore the best paperback sizes for different types of books, ensuring your work fits perfectly on any shelf and is easy for readers to enjoy. You can check it out for practical advice on selecting the ideal book size for your collection.

Factors More Crucial Than Quantity

So if numbers don’t define libraries, what does? Several elements matter far more than how many books you own.

Purpose and Mission come first. What is the collection for? A public library exists to serve community information needs and foster literacy. An academic library supports teaching and research. A law library provides legal resources to practitioners. A personal library might support professional development, family education, or pure reading pleasure. Without a defined purpose, you’re just accumulating things.

Curation and Relevance matter immensely. Is the collection thoughtfully selected and useful for its intended purpose? A medical library with 500 current, authoritative texts is more valuable than one with 2,000 outdated volumes. A children’s library with 100 age-appropriate, engaging books serves its purpose better than one with 1,000 random titles.

Organisation and Accessibility determine whether your collection actually functions. Can users find what they need? Is there a logical arrangement, whether that’s a formal classification system like Dewey Decimal or a simpler approach based on genre and author? Are materials catalogued so you know what you own? If you can’t locate books when you need them, the collection isn’t serving its purpose regardless of size.

Stewardship and Preservation reflect commitment to the collection’s longevity. Are books protected from damage? Are they stored properly? Is there attention to their physical condition? A library, unlike a temporary collection, implies some degree of permanence and care.

Community Engagement extends beyond institutional libraries. Even personal libraries often have a social dimension, lending to friends, sharing recommendations, using the collection as a gathering point for discussion. Community libraries explicitly build this into their mission.

These factors explain why the question how many books is considered a library can’t be answered with a single number. A 200-book collection that excels in purpose, curation, organisation, preservation, and community engagement is more of a library than a 5,000-book collection that fails in these areas.

Types of Libraries & Their Collection Sizes (Approximate)

Understanding different library types helps contextualize collection sizes. Here’s an overview of the spectrum from massive national institutions to small community initiatives.

| Library Type | Primary Purpose | Typical Collection Size (Approx.) | Key Characteristics |

| Public Library | To provide open access to resources for communal learning, growth, and information. | 50,000 – 500,000+ items (physical & digital) | Serves the general public, often funded by taxes, free access, diverse collections, community programmes. |

| Academic Library | To support the educational and research needs of a college or university. | 1,000,000 – 9,000,000+ items | Serves students, faculty, researchers; specialised collections, academic databases, research support, archives. |

| School Library | To support the curriculum and foster reading for pleasure amongst K-12 students. | 5,000 – 50,000+ items | Serves students and teachers; age-appropriate collections, curriculum support, literacy programmes, often run by a school librarian. |

| Special Library | To provide resources and specialised information for a specific, focused community or organisation (e.g., law firms, hospitals, museums, corporate R&D). | 1,000 – 100,000 items (highly specialised) | Serves a niche audience; very specialised collection, often includes unique databases and archives, geared towards specific professional or research needs. |

| Home / Personal Library | To provide access to personally collected resources for personal education, entertainment, and occasionally, shared learning. | 100 – 10,000+ items | Privately owned, organised for personal use, may have a specific focus (e.g., fiction, history, cookbooks), accessibility is typically limited to owner/close contacts. |

| Micro Library | To provide hyper-local, specialised resources and foster community connection. | 20 – 500 items | Often volunteer-run, highly accessible (e.g., Little Free Library), niche collections, emphasizes community sharing and engagement over quantity. |

| Digital Library | To provide access to electronic resources (e-books, journals, databases, multimedia) without physical limitations. | Varies greatly, from thousands to millions of resources | Entirely virtual, accessible online, often subscription-based for institutions, focuses on digital content and remote access. |

These ranges are approximate and can vary dramatically based on funding, mission, and historical context. The Library of Congress, for example, holds over 170 million items. Harvard Library, one of the world’s largest academic collections, contains over 17 million volumes. At the other extreme, successful community micro-libraries operate with fewer than 100 books.

What’s striking isn’t the variation in size, it’s that each type successfully serves its intended purpose. A micro-library with 75 carefully selected children’s books in a neighborhood that lacks a public library has genuine impact. It’s not “less of a library” than a massive research institution; it’s a different type of library serving a different need.

Spotlight: Micro-Libraries & Unconventional Collections

Some of the most inspiring library initiatives are also the smallest. Little Free Libraries, those small weatherproof boxes on posts in front gardens and parks, typically hold 20-40 books at a time. They operate on a simple principle: take a book, leave a book. No formal cataloguing, no professional staff, minimal organisation. Yet they function as genuine libraries within their communities.

Consider other unconventional examples. Tool libraries lend out equipment for home repair and building projects. Seed libraries allow gardeners to “borrow” seeds, grow plants, harvest new seeds, and return them to the collection. A mobile library on a bicycle might carry only 50 books but bring literacy resources to underserved areas. A zine library preserves and shares self-published, often radical, independent publications that mainstream libraries might overlook.

These collections prove that how many books constitutes a library is the wrong question. What matters is impact, access, and community service. A tool library with 200 items might serve its neighborhood more meaningfully than a 10,000-book personal collection that never leaves its owner’s basement.

What Truly Constitutes a Library (Beyond Quantity)

Purpose and Mission: The Guiding Star

Every functional library begins with purpose. Why does this collection exist? Who does it serve? What needs does it address?

For institutional libraries, mission statements make this explicit. A public library might commit to “providing equitable access to information, supporting lifelong learning, and fostering community connection.” An academic library’s mission centres on supporting scholarship and teaching. These aren’t just bureaucratic formalities, they guide every decision about what materials to acquire, what services to offer, and how resources are allocated.

Personal and community libraries benefit from the same clarity. If you’re building a home library to support your children’s education, that purpose shapes what you collect, age-appropriate materials, curriculum support, books that encourage reading for pleasure. If your goal is maintaining professional knowledge in your field, you’ll curate differently, current publications, reference works, specialised journals.

Expert Tip: Community Engagement is Powerful. For public or community libraries, actively solicit input from your users to build a collection that truly serves their dynamic interests and educational needs.

Purpose determines whether 200 books are plenty or 2,000 aren’t enough. A specialised law library supporting a small firm might need fewer volumes than a generalist trying to cover all of human knowledge.

Curation and Collection Development

Curation is the thoughtful, ongoing process of building and maintaining a collection. It’s not just buying books, it’s selecting materials that serve your defined purpose, ensuring quality and relevance, and regularly evaluating what should remain and what should go.

Professional libraries have formal collection development policies. These documents specify subject areas to collect, depth of coverage, formats to include, criteria for selection, and guidelines for weeding (removing) outdated or damaged materials. It’s systematic and intentional.

Personal libraries benefit from similar intentionality, even if less formal. Ask yourself: Does this book serve my library’s purpose? Is it something I’ll actually use or reference? Does it fill a gap in my collection or simply duplicate what I already own? Will it remain relevant, or is it trendy content that will date quickly?

This mindset transforms random book buying into genuine collection building. It also explains why a well-curated collection of 500 volumes can be more valuable than a haphazard accumulation of 5,000. Quality and relevance trump raw numbers.

The process includes deselection, removing books that no longer serve the collection’s purpose. Libraries weed damaged items, outdated information, and materials that haven’t circulated in years. Personal collections benefit from the same practise. If you haven’t opened a book in a decade and can’t imagine a scenario where you would, it’s taking up space that could house something more useful.

As you thoughtfully curate and expand your library, you may also begin to consider adding your own works to the collection. If you’ve been working on a manuscript or have always dreamed of sharing your story with the world, the next step is understanding how to navigate the world of publishing. The process can feel overwhelming, but with the right guidance, it’s entirely achievable. To get started, take a look at How to Publish a Book: Guide to Book Publishing in the UK. This comprehensive guide will walk you through everything you need to know about getting your book into the hands of readers, from editing and design to distribution and promotion.

This is where the expertise of a professional book ghostwriter might also make a difference for you. It is very important that you learn the top benefits of hiring a professional book ghostwriter to help you explore how a skilled ghostwriter can bring your ideas to life, saving you time and effort while ensuring your story is told in the best way possible. If you’ve ever thought about writing but felt overwhelmed, they can also guide how to write a book about your life and help you turn your vision into a polished, professional book.

Organisation and Cataloguing Systems

Organisation transforms a pile of books into a functional resource. Without systematic arrangement, even modest collections become frustrating to use. You know you own a book but can’t find it. You forget what you have and buy duplicates. Research becomes impossible because relevant materials are scattered unpredictably.

Professional libraries use standardized classification systems. The Dewey Decimal System organizes materials by subject across ten main classes, subdividing into increasingly specific categories. The Library of Congress Classification uses a similar but more complex approach, particularly suited to large academic and research collections. These systems enable anyone familiar with them to navigate any library using the same classification.

Expert Tip: Organisation is Foundational. Implement a consistent cataloguing system (e.g., Dewey Decimal, Library of Congress, or a simpler home system) from the very beginning to ensure long-term manageability.

Personal libraries don’t necessarily need this level of complexity. Many people organise by genre (fiction, biography, history, science), then alphabetically by author within each category. Others arrange by subject matter relevant to their needs. Some organise by size or colour, though these approaches sacrifice findability for aesthetics.

What matters is consistency and logic. Your system should make sense to you and anyone else who might use the collection. It should make finding specific books straightforward. And ideally, it should scale, simple enough to implement now but capable of accommodating growth.

Cataloguing, maintaining records of what your library contains, complements physical organisation. This can be as simple as a spreadsheet listing titles, authors, and locations. More sophisticated approaches use dedicated software that enables searching by multiple criteria, tracks lending, and maintains purchase information.

Accessibility and Usability

A library is only as valuable as its accessibility. Materials that can’t be found or reached serve no purpose, regardless of how numerous or high-quality they are.

Physical accessibility starts with layout. Are shelves at reachable heights? Is there adequate lighting for browsing? Can people move comfortably through the space? For home libraries, this might mean ensuring your most-used books are at eye level rather than requiring a stepladder. For community libraries, it means considering whether the space accommodates wheelchairs and serves diverse physical abilities.

Intellectual accessibility involves making the collection discoverable. This includes clear labeling, the cataloguing system we discussed, and helpful organisation that anticipates how users think about materials. If your library includes a cookbook collection, arranging by cuisine type might be more useful than alphabetically by author.

For lending libraries, whether institutional or informal, policies matter. What are the terms for borrowing? How long can materials be kept? What happens if something is damaged or lost? Clear, consistent policies make libraries more usable by eliminating uncertainty.

Expert Tip: Accessibility Matters Immensely. Ensure books are easily discoverable and physically/digitally accessible to your target audience, whether through clear labeling, a cataloguing system, or thoughtful layout.

Online catalogues extend accessibility dramatically. Most institutional libraries now offer searchable digital catalogues that tell users what’s available, where it’s located, and whether it’s currently checked out. Personal library software can provide similar functionality for home collections, particularly useful for larger collections spread across multiple rooms.

Stewardship and Preservation

Libraries, by definition, look towards the future. They’re not just current resources but repositories meant to endure. This requires stewardship, the responsibility of maintaining and protecting collections.

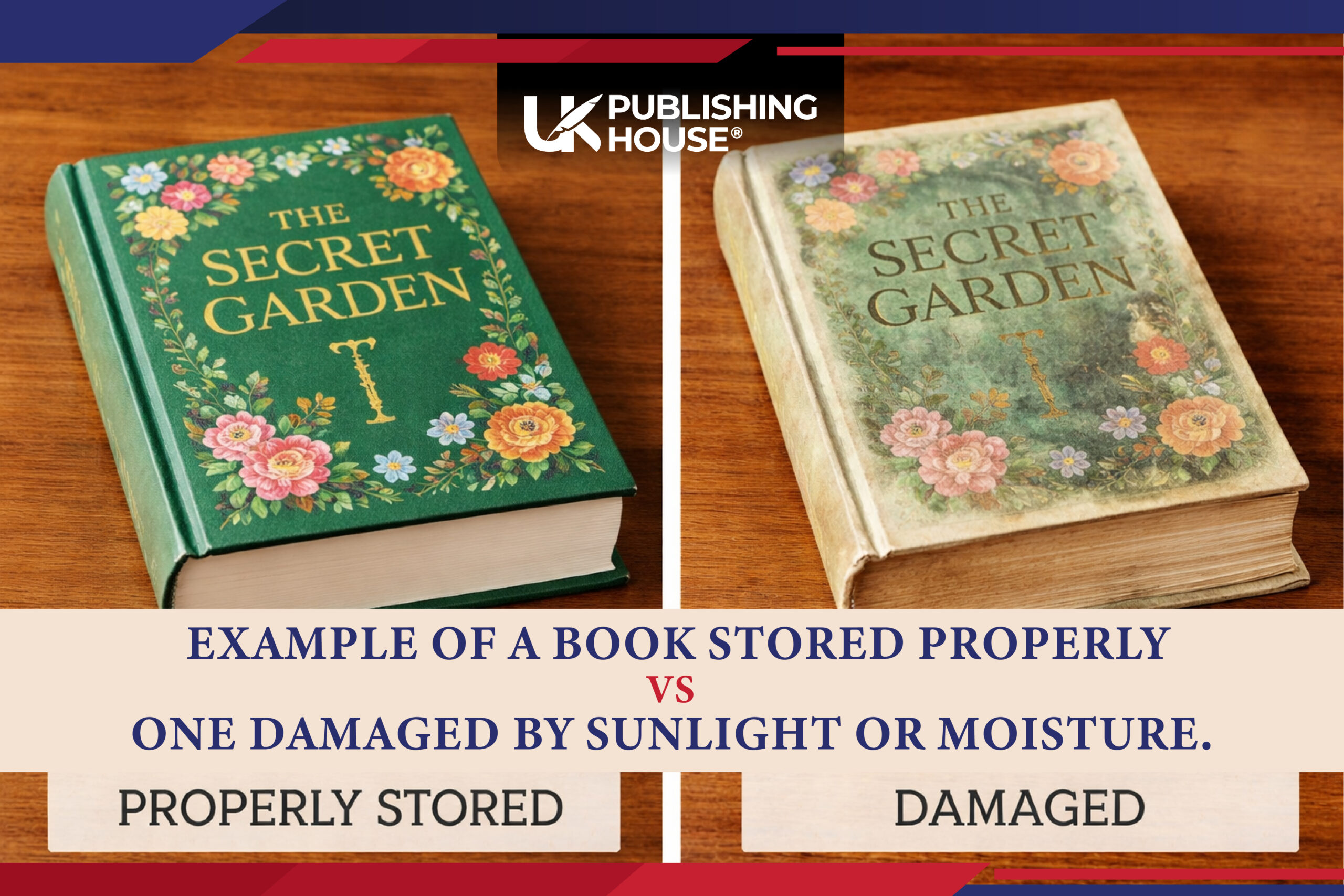

Professional preservation involves environmental controls (temperature and humidity management), pest prevention, handling protocols, repair and conservation techniques, and security measures. Major libraries employ preservation specialists and invest substantially in protecting rare and fragile materials.

Home libraries need less elaborate measures but benefit from basic preservation awareness. Books are damaged by direct sunlight (which fades covers and degrades paper), high humidity (which encourages mould), extreme dryness (which makes paper brittle), and temperature fluctuations. Simple practices make a difference: keep books away from windows, maintain stable indoor climate, store them upright (lying books flat for extended periods damages spines), and handle them with clean hands.

Expert Tip: Practice Basic Preservation. Learn fundamental book care and storage techniques to protect your collection from environmental damage, pests, and wear, ensuring its longevity.

For valuable or rare items, archival-quality materials matter. Acid-free storage boxes protect books from light and environmental damage. Archival book covers guard against wear while remaining gentle on original covers. These aren’t necessary for all books, but they’re worthwhile for items you particularly value or hope to pass down.

The Role of Staff and Librarianship

The human element distinguishes many libraries. Professional librarians aren’t just people who check out books, they’re information specialists trained in organising knowledge, helping users navigate resources, developing collections, and teaching information literacy.

In institutional settings, librarians perform reference work (helping users find information), instruction (teaching research skills), collection management, programming (community events and educational offerings), and increasingly, digital services and technology support. They’re the interface between vast information resources and people trying to use them effectively.

Not every library needs professional librarians. Small community libraries often operate successfully with dedicated volunteers. Personal libraries obviously don’t require professional staff. But the principle remains valuable: someone needs to take responsibility for maintaining organisation, ensuring accessibility, and helping users navigate the collection.

For community libraries, recruiting volunteers with enthusiasm and basic organisational skills can work well. For personal libraries, simply designating yourself as your own librarian, taking seriously the responsibility of maintaining and curating your collection, brings focus and intentionality to the work.

Professional librarians are generous with advice. If you’re building a community library or a substantial personal collection, reaching out to librarians at your local public or academic library for guidance is worthwhile. They understand these systems and are usually happy to share knowledge.

The Evolving Role of Non-Book Materials & Digital Resources

Expanding the Definition of a ‘Collection’

Modern libraries have exploded beyond traditional book collections. Walk into a contemporary public library and you’ll find much more than printed volumes.

This evolution reflects how people actually consume information and media today. Reading happens across formats, print books, e-books, audiobooks. Research draws on journal databases, digitized archives, online repositories. Learning involves multimedia, documentaries, educational streaming content, interactive digital resources. Recreation includes films, music, video games.

Libraries have adapted accordingly. The question of how many books makes a library becomes almost quaint when libraries house vast digital collections alongside physical materials. What “counts” has expanded dramatically.

Digital Integration: E-books, Audiobooks, Databases

E-books and audiobooks present both opportunities and challenges for libraries. They offer instant access without physical storage constraints, can serve users remotely, and never suffer physical wear. But they also involve complex licensing rather than ownership, require compatible devices and technical support, and often cost more than institutional libraries would pay for print equivalents.

Most public and academic libraries now offer substantial digital collections through services like OverDrive, Hoopla, or Libby. Users can browse, check out, and download materials directly to their devices. These digital titles are part of the library’s collection just as much as physical books, even though they occupy no shelf space.

Research databases represent another major category. Academic libraries subscribe to hundreds of specialised databases, JSTOR for scholarly journals, PubMed for medical literature, Westlaw for legal research, and countless others. These resources are enormously expensive but absolutely essential for serious research. They’re part of what you’re accessing when you use an academic library, even if you never touch a physical book.

Expert Tip: Embrace Digital Resources. Modern libraries integrate e-books, audiobooks, online databases, and internet access; physical books are only one part of a comprehensive collection.

Personal libraries are incorporating digital elements too. Many people maintain collections of e-books alongside physical books, curating both with equal care. Some use cloud storage to organise digital articles, PDFs, and other resources they’ve accumulated. The principles remain the same, intentional selection, organisation, accessibility, even as the format changes.

Multimedia and Beyond: Films, Music, Games, Tools

Public libraries increasingly function as community resource centres that happen to include lots of books. Many lend films, music CDs, and video games. Some offer digital streaming services. You might find educational kits for children, mobile hotspots for internet access, or equipment like projectors and cameras.

This expansion reflects evolving community needs. In areas with limited broadband access, libraries provide internet connectivity. In under-resourced communities, they offer materials people couldn’t otherwise afford. They’re adapting to serve their communities however needed.

Some libraries have gone further into non-traditional territory. Tool libraries lend out drills, saws, and construction equipment. Maker spaces provide 3D printers, laser cutters, and electronics workbenches. Kitchen libraries lend baking equipment and specialty tools. Toy libraries support families with young children. Seed libraries promote gardening and plant diversity.

Expert Tip: Consider Non-Book Media. Beyond traditional books, items like films, music, games, educational kits, or even tools can significantly enhance a library’s offerings and community value.

These developments challenge traditional definitions but embody library principles. They’re organised collections of resources, curated to meet user needs, made accessible to defined communities, and maintained through ongoing stewardship. The format is different, but the underlying concept is consistent.

Accessibility in the Digital Age

Digital resources create new accessibility challenges. Not everyone has devices to access e-books or reliable internet for streaming. Digital materials often involve DRM (digital rights management) that restricts how they can be used. Licensing terms can be restrictive, and content can disappear when agreements end.

Libraries work to address these barriers. Many lend e-readers preloaded with books. They provide computer access and Wi-Fi. They negotiate better licensing terms with publishers. They advocate for fairer digital access policies.

For personal digital libraries, accessibility concerns differ but remain real. File formats become obsolete. Cloud services shut down. Hard drives fail. Good digital stewardship involves backup systems, file format awareness, and thinking about long-term access, not just accumulation.

Historical Context: How Library Standards Have Evolved

Ancient Libraries to Modern Institutions

The concept of a library is ancient, but what that meant has transformed dramatically. The Library of Alexandria in ancient Egypt aimed to collect all knowledge in the known world, perhaps 400,000 scrolls at its height. Access was restricted to scholars, and “books” were hand-copied papyrus scrolls.

Mediaeval monastic libraries preserved knowledge through the Dark Ages, but these were small, private collections focused on religious texts. A monastery might house a hundred manuscripts, each painstakingly copied by hand. Access was limited to religious scholars.

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century fundamentally changed libraries by making books affordable and reproducible. Collections could grow exponentially. The idea of public access emerged gradually, with subscription libraries (where patrons paid for access) appearing in the 18th century.

True public libraries, free and open to all, are a relatively recent development, mostly emerging in the 19th century. The United States’ public library movement, championed by figures like Andrew Carnegie, was revolutionary in asserting that everyone deserved access to information regardless of wealth or status.

Changing Metrics and Expectations

Throughout this evolution, definitions of libraries changed. Ancient standards emphasised size and comprehensiveness, great libraries aimed to collect everything. Mediaeval standards prioritized preservation and religious significance. Early modern standards emphasised scholarly utility.

Public libraries shifted the emphasis to access and community service. Size still mattered, but relevance to actual user needs became paramount. Better to have 10,000 books your community would actually use than 100,000 that gathered dust.

Digital resources have further transformed standards. Collection size now includes items never physically present in the building. A small rural library with a modest physical collection might offer users access to millions of items through digital subscriptions and interlibrary loan networks.

This historical perspective reveals that how many books is a library has never had a consistent answer. The concept adapts to technological capabilities, social values, and community needs. Contemporary definitions emphasise purpose, service, and access more than absolute size, a return, in some ways, to ancient principles about what libraries fundamentally exist to do.

How to Build Your Own ‘Library’: From Collection to Curated Resource

Defining Your Purpose and Audience

Before acquiring a single book, clarify why you’re building this collection. Are you supporting your professional development? Creating educational resources for your children? Building a community resource for neighbors? Pursuing a personal passion for a particular subject?

Your purpose shapes everything else. A library focused on children’s literacy requires different materials than one supporting graduate-level research or one celebrating a local community’s history.

Consider your audience, even if that’s just yourself. What are their needs, interests, and reading levels? How will they interact with the collection? What gaps in existing resources does this library fill?

Expert Tip: Start Small, Grow Smart. Don’t feel pressured to acquire thousands of books immediately; build your collection thoughtfully, sustainably, and in alignment with your defined purpose and resources.

Write your purpose down. It doesn’t need to be formal, but articulating it helps maintain focus. When you’re tempted by an irrelevant but appealing book, refer back to your purpose. Does this serve what you’re building? If not, skip it.

Curating Your Collection Thoughtfully

With purpose clear, begin curating. This is selective, intentional acquisition, not random accumulation.

Consider relevance to your mission. Each item should serve your defined purpose. Quality matters, seek well-written, authoritative, engaging materials rather than just filling space. Diversity strengthens collections, offering varied perspectives and covering topics comprehensively. Physical condition shouldn’t be ignored either; damaged books require immediate repair or replacement.

Acquisition strategies vary by budget and purpose. Buying new ensures current information and good condition but costs more. Used book sales, charity shops, and online marketplaces offer bargains but require more effort to find quality items. Donations can build collections quickly but demand careful vetting, accept only materials that fit your purpose and meet quality standards.

For community libraries, establish clear acquisition criteria. Make donation guidelines public so people know what you need and what you can’t accept. Be willing to decline materials that don’t serve your mission, even if they’re free.

Organising for Discoverability

As your collection grows, organisation becomes essential. Start simple, but be consistent.

For small personal libraries (under 500 books), organising by broad category and then alphabetically by author often suffices. Fiction might be separated from non-fiction, with non-fiction subdivided by subject (history, science, biography, cooking, etc.). Within each category, alphabetize by author’s last name.

Larger personal collections might benefit from simplified Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress systems. Both have resources explaining how to classify books. It’s more work initially but pays off in findability.

Community libraries should use a recognized system, even if simplified. This helps volunteers and users navigate consistently. Many small libraries use basic Dewey Decimal for the main collection and simpler genre divisions for popular materials.

Ensuring Accessibility

Organisation enables accessibility, but additional steps make collections truly usable.

Create a catalogue, even a basic one. For small collections, a spreadsheet listing title, author, subject, and shelf location works. Larger collections benefit from library cataloguing software that enables keyword searching, tracks items checked out, and maintains bibliographic information.

Label clearly. Shelf markers should be visible and logical. If you’re using a classification system, small labels on book spines help (available as adhesive labels or can be written on paper labels).

For personal libraries used primarily by you, you can customise for your own needs. But if others will use the collection, family members, students, community members, design for them. Can they find materials independently? Is the system intuitive? Are instructions available?

Lending policies matter for shared collections. How long can materials be borrowed? Is there a limit on number of items? What happens with damaged or lost books? Write policies down and make them accessible.

Basic Preservation Techniques

Protecting your collection ensures it remains usable long-term.

Environmental considerations come first. Avoid direct sunlight, which fades covers and degrades paper. Maintain stable temperature and moderate humidity. Avoid basements prone to flooding or dampness and lofts with temperature extremes.

Shelve books properly. Stand them upright, supported by bookends if necessary. Avoid packing shelves too tightly (which damages spines when removing books) or too loosely (which lets books lean and warp). Very large or heavy books can be shelved horizontally, but limit stacking to two or three books to avoid crushing lower volumes.

Handle books with clean, dry hands. Turn pages gently, especially with older or fragile volumes. Never force a book open flat, which damages the spine.

Regular maintenance prevents problems. Dust shelves and books periodically. Check for signs of pest damage (silverfish, bookworms). Examine bindings and repair minor damage before it worsens.

Expert Tip: Practice Basic Preservation. Learn fundamental book care and storage techniques to protect your collection from environmental damage, pests, and wear, ensuring its longevity.

Fostering Community & Engagement

If you’re building a community library, engagement is essential.

Involve your community from the start. Solicit input on what materials people want. Host donation drives. Create volunteer opportunities for organising, staffing, or maintenance.

Programming brings people together around books. Book clubs, story times for children, author events, skill-sharing workshops, these activities make the library a gathering point, not just a storage facility.

Promote your library. Use social media, neighborhood listservs, community bulletin boards. Partner with schools, churches, or community centres to reach more people.

Make it welcoming. Comfortable seating, good lighting, and friendly interactions matter. If people feel comfortable and welcome, they’ll return and spread the word.

Expert Tip: Consult Library Professionals. Reach out to local librarians or library science educators for advice, resources, and potential partnerships, especially when embarking on a new library initiative.

As we’ve explored, a true library is more than just a collection of books; it’s about purpose, organisation, and accessibility. Similarly, UK Publishing House is dedicated to helping authors bring their stories to life with intention and professionalism. Offering a full range of services, from ghostwriting and editing to book design, publishing, and marketing, UKPH ensures that each book not only reaches its audience but also makes a lasting impact. Whether you’re a first-time author or a seasoned writer, UK Publishing House provides the expertise and support to help your work find its place in the world.

The last thing you need to consider before building your library, whether for personal use or as a community resource, is to understand the importance of promoting and sharing your own written works. One essential step for authors looking to establish their presence is setting up a professional profile on platforms like Amazon Author Central. This tool helps authors manage their book listings, track sales, and engage with readers. To get started, explore Amazon Author Central UK: Complete Guide for Authors to learn how to leverage this powerful resource and take your writing career to the next level.